There are pretty several ways to discover new drugs that can influence our health differently. Of most importance is modafinil – a drug dubbed as a “smart pill” that does amazing things to various individuals – both the sick and healthy ones.

Now, it’s wake-up time. Say goodbye to drowsiness with the medicine that wakes you up. This guide talks about modafinil use to stay awake, especially among the military, testing this drug against sleep, the public reaction to it, and revelations about Dale Edgar’s modafinil studies.

Using Drugs to Stay Awake Among Military

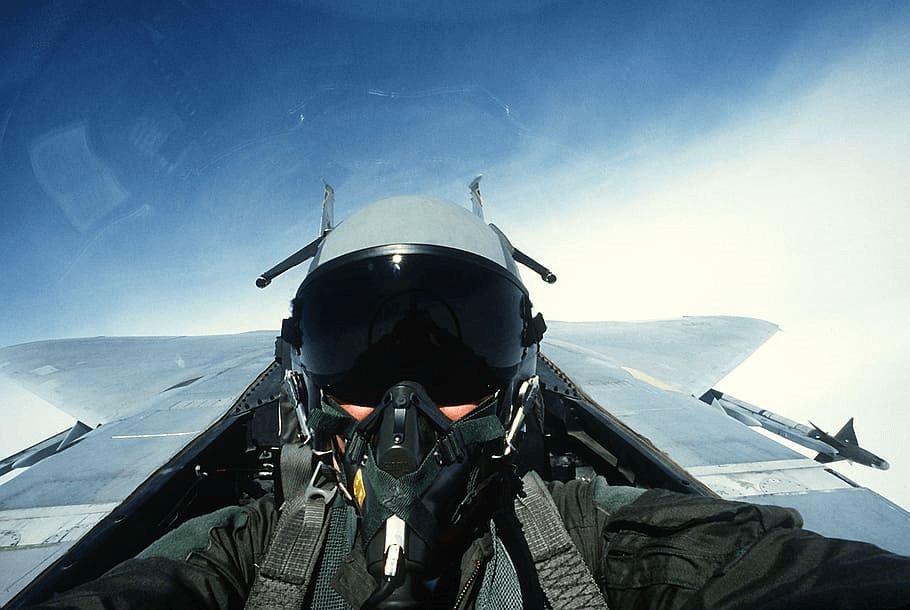

There are various drugs that wake you up. Modafinil was first discovered as a wakefulness-promoting agent. In the US military, this medicine is approved for use on certain Air Force missions. As of November 2012, it became the only medicine approved by the US Air Force as a potent “go pill” for fatigue management and an alternative to amphetamine drugs [1].

A “go pill” alludes to a wakefulness-promoting agent primarily used to manage fatigue, particularly in a military combat-readiness context. It’s juxtaposed with a “no-go pill” – a class of meds used to promote sleep in support of combat action. Taking such a tablet by the military ensures they achieve sufficient rest in preparation for forthcoming tasks or rest & recovery.

A “go pill” is widely known to contain amphetamine or modafinil:

- amphetamine is a strong psychostimulant med having been used historically, such as during the Second World War (WW2), but is no longer officially agreed as satisfactory for use by the U.S. Air Force;

- modafinil is a safe and very effective wakefulness-promoting med (a nootropic or eugeroic) that’s now dubbed as the “world’s first safe smart drug.” This med is publicized by healthy individuals – nootropic enthusiasts using it as a cognitive enhancer or productivity booster in its wake [2].

In November 2012, drugs officially approved as “no-go” meds by the U.S. Air Force for Special Operations include temazepam (Restoril®), zaleplon (Sonata®), and zolpidem (Ambien®).

Worldwide, militaries have used or are currently using various psychoactive meds to enhance the execution of soldiers at a mission by suppressing hunger, boosting the potential to sustain effort without food, suppressing fear, enhancing and lengthening wakefulness & concentration, ameliorating reflexes and memory-recall, and reducing empathy, among other things.

To various militaries, modafinil does the same job as amphetamine does. In 2011, the Indian Air Force declared that this “smart pill” was part of their meds used in contingency plans. This medicine was displaying no serious negative effects and had already been tried by pilots in the USA [3].

The use of modafinil by the US military became evident in January 2003. This was when the U.S. Air Force majors Harry Schmidt & William Umbach (from Illinois Air National Guard) faced court-martial after a friendly fire incident that took place in Afghanistan, which killed several people.

This matter was taken to court. During a pretrial hearing, Umbach’s lawyer revealed confidential information pertaining to one of the Pentagon’s unique secrets – the pilots (who caused an accident) had been on speed the moment they dropped the fatal bomb.

According to the lawyer, the pilots’ judgment was impaired because their superiors influenced them to make ready for the mission by taking Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine), a convention he described as common. Although it works, this medicine is no longer approved.

Dextroamphetamine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant & an amphetamine enantiomer prescribed for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. This drug is also used as an athletic performance and cognitive enhancer (just like what modafinil does) and recreationally as an aphrodisiac and euphoriant [4].

During the court hearing, charges against Harry Schmidt & William Umbach were dropped. Why? The revelation prompted public outrage.

The pilots were using the recommended pills to remain alert. This came as no surprise to anyone. Officers were known to always seek effectual ways to keep their troops awake. The Chinese sentries along the Great Wall administered the herb “ma huang” (ephedrine). Similarly, the Air Force itself was widely known to be using the “go pills” since WW2.

Preparing for their mission over Afghanistan & Iraq, the U.S. Air Force gave Schmidt and Umbach an F-16 fighter jet coupled with something worth mentioning — a prescription pill known as uppers or speed. An investigation found the speed pills were a standard issue for Air Force fighter pilots. They helped them to prolong their wakefulness on long combat sorties.

Schmidt was an upskilled top gun fighter pilot called to join his colleague in a mission to Afghanistan. Umbach was called up at the same time, leaving behind his full-time job as a United Airlines pilot.

They both viewed their military service with pride. “Being military, we have always lived in the flight pattern. And when we’d see the jets go over it was always a great, wholesome feeling of pride,” said Schmidt’s wife, Lisa.

Umbach said he felt a commitment to serve: “It’s sort of a patriotic thing. I feel like it’s something that I should do.”

But what befell in the skies over Kandahar on the eve of April 17, 2002, changed Umbach and Schmidt’s lives forever and brought them to face a court-martial. This was only due to the “go pills.”

They were tacitly reintroduced to the “go pills” after being proscribed in 1992 by Gen. Merrill McPeak who was then the Air Force Chief of Staff. “In my opinion, if you think you have to take a pill to face something that’s tough, you’re in the wrong business,” McPeak said.

Then, a tragic situation happened. Although the controllers in an Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) plane overhead informed Schmidt to detain his fire against an enemy, he was uncontrollably convinced that they were under attack and abruptly let the bomb go.

“A combat sortie that’s seven or eight or nine hours is very challenging. You have highs and lows,” said Gen. Daniel Leaf – a 2-star general & a former combat pilot who was designated to defend the use of the “go pills.” According to him, the pills prescribed to their military personnel on various missions were only given in small controlled doses.

But, no matter the dose, the drug was not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to combat fatigue. However, the “go pills” were listed by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule II narcotic – just in the same class as cocaine.

Leaf said they were not used for recreation. He described the “go pill” as a “medical tool.” “Our medical community has carefully evaluated their use, deemed it appropriate. I agree. I believe they’re effective. I believe they’re well-administered,” he said.

But that’s not what Umbach & Schmidt pronounced when they arrived at their post in Kuwait. According to their defense lawyers, the pilots were advised by their superiors they could be found improper to carry out their mission unless they took the pills.

Capt. Matt Skobel, Umbach’s military lawyer, voiced: “These missions were at the limit of the pilots’ physical and mental endurance. And these pills were required to allow them to do it.”

According to the U.S. military, pilots were allowed to sign up on a clipboard for 6 “go pills” at a time and were advised to use them as needed. But Umbach depicted that he knew the rules from his civilian job that such tablets were strictly prohibited for commercial airline pilots.

However, he & Schmidt used the pills on their April 17, 2002, night mission over Afghanistan space about an hour before a fatal strike happened, according to Schmidt’s defense lawyer Charles Gittins.

“An hour after he took the pills …he would have been feeling the maximum serum level in his blood,” Gittins said. It was then under the full effect of the “go pills” that they spotted weapons fire near the Kandahar Air Base as can be ascertained on the cockpit tapes procured by 20/20. “I’ve got some men on a road with a piece of artillery firing at us. I’m rolling in self-defense.” Schmidt’s voice was heard saying on the tape. It was only after Schmidt dropped the bomb that he was informed the target was not the enemy. The outcome? The bomb hit a squad of Canadian soldiers, killing 4 of them and wounding 8. This was what the military referred to as “friendly fire.”

The two pilots had not been informed the Canadian soldiers would be performing a night live-fire training exercise in the area, even though the Canadian military had satisfactorily informed the U.S. military. A joint American + Canadian investigation blamed the two U.S. pilots for being too swift to open fire.

Robert DuPont, a former White House Drug Czar, said the pills taken by the two soldiers might have prompted them to “a quick conclusion that is wrong.” He voiced that he wouldn’t rule out that the “go pills” might have been a factor in the lethal incident.

Nonetheless, the US Air Force pronounced the “go pills” taken by Schmidt and Umbach as being accountable in any way.

“These men are patriots, these men were sent to fight a war and they’re put in a situation where it’s either take these pills or you don’t fly,” Skobel said. “It’s not a choice at all.”

Testing Modafinil Against Sleep

In the early 2000s, Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funded a program aimed at studying natural alertness mechanisms like that of the white-crowned sparrow, which can stay awake for up to 2 weeks during migration. Its goal was to produce a GI (a private soldier in the US army) who could go without sleep for 7 consecutive days.

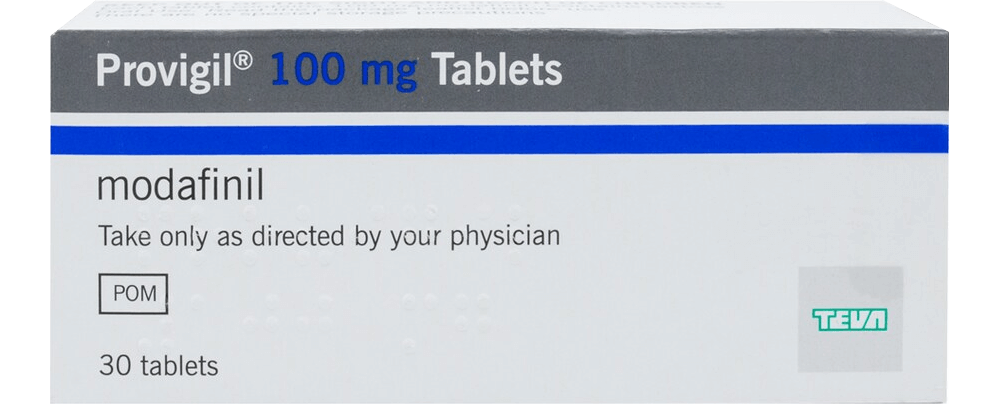

In the same period, Aeromedical Research Laboratory (which is part of the U.S. Army) began testing modafinil – an antisleep agent discovered by the French firm, Lafon, and sold by Pennsylvania medicine maker, Cephalon, under the brand names, as Provigil®.

How long can you stay awake on modafinil? It can keep users up for 2 or 3 days at a stretch with negligible negative effects and minimal risk of addiction. Once administered, it takes about 30 to 60 minutes for its effects to kick in and its duration of effect is about 12–15 hours.

Modafinil is currently a “smart drug” taken by nootropic enthusiasts as a cognitive enhancer. This medicine was approved by the FDA in 1998 as a remedy for sleep disorders due to narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder (SWSD), and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Due to modafinil’s wider research, safety, and broader applications, medical specialists can prescribe it as a potent remedy for various health conditions outside its approved use. This medicine has been used to treat excessive sleepiness in patients with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and multiple sclerosis; it’s also been proven to help cocaine addicts kick the habit.

There are other possible uses of modafinil that doctors can prescribe such as ADHD, depression, myotonic dystrophy, age-related memory decline, post-anesthesia grogginess, multiple sclerosis-induced fatigues, cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, methamphetamine (“ice”) abuse, idiopathic hypersomnia, jet-lag, apathy in the elderly, cancer-associated fatigue & opioid-induced sedation, weight loss, etc.

The French Foreign Legion administered modafinil in the Gulf War, and although the Pentagon didn’t comment about their use of this drug, a majority of news outlets depicted that coalition troops were prescribed it en route to Baghdad in 2003.

But the modafinil pill isn’t just for the sick people and soldiers anymore. In 2003, Cephalon (a parent company – Teva Pharmaceuticals) submitted to the FDA a supplemental application that would give medical specialists a free hand to prescribe Provigil medicine for lesser sleep disorders, such as shift-work drowsiness.

In those early days, without that approval by the FDA, modafinil began attracting a wider market: students, truckers, top CEOs, IT professionals, and others used it as a cognitive enhancer, wakefulness promoter, and productivity booster.

Public Reaction to This New Discovery

In the mainstream media, the uncovering of a chemical that was key to a 24/7 society sparked predictable concerns and worries. But Provigil recreational pill had no appeal.

Unlike amphetamines, which invigorate the whole CNS, modafinil does not jazz up users. It straightforwardly shuts off their sleep jones. It does not produce euphoria – something common in cocaine – or the bliss from ecstasy. It just succors people to stay awake and benefits healthy individuals with enhanced cognition improved memory, and other characteristics it comes with.

The medical establishment from the Big Pharma was excited about Provigil exactly because it was the first efficacious stimulant with no outstanding prospective for abuse.

The selfsame research that led to the birth of stay-awake pills was believed to revolutionize the ideal remedy for sleep disorder conditions at the opposite end of the spectrum: insomnia. Scientifically, modafinil’s merit was in its precision.

Although its exact mode of action is not thoroughly comprehended, modafinil affects only the urge to stay awake to the extent of promoting cognitive function, productivity, etc.

Other companies applied the same basic breakthrough after modafinil. Cephalon, Neurocrine Biosciences, and a trailblazer in the field, Hypnion, were aiming to develop compounds similar to but more efficacious than Provigil.

The effect? Some said that within a decade, continuous alertness pills could be available over the counter. The expertise of aiming at a specific receptor in the human body would likely lead the way to superior sleeping pills.

Those looking for a restful night could easily find the medicine in any pharmacy, and for patients with chronic insomnia, a health condition affecting 20 to 40 percent of U.S. residents, could be a thing of the past.

About the Dale Edgar’s Modafinil Researches

“It’s time for a revolution,” voiced Dale Edgar, a joint founder of Hypnion, a neuroscience medicine discovery & development company established in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 2000. Hypnion designs and develops novel therapeutics for the treatment of CNS disorders, remedies for sleep- and wake-alertness disorders, and circadian rhythm abnormalities.

Dale Edgar is the ultimate medicine scientist whose comprehensive research on sleep has helped put down the groundwork for modafinil.

About modafinil and other drug research, Dale Edgar said, “The drugs will do for sleep disorders what Prozac did for depression.”

The Hypnion company used rats and mice as the test subjects for its new sleep-wake medicines. They kept a check on the results with a medicine-testing system known as Score 2000. It was designed to receive radio signals & track reactions remotely over a network. The study monitored the habits of rats using data streaks across terminals: movement, vital signs, feeding habits, and, most salient, sleep patterns.

Together with a colleague at Stanford, Edgar developed the system after a grant from the U.S. Air Force & the Department of Defense. They were in quest of medical sensing applications for the U.S. troops in the field.

Hypnion was so extreme in stealth mode that some scientists in sleep science study didn’t even know it existed. Noticeably, Edgar made his mark way back in the mid-90s, under contract for Cephalon. He used an earlier model of Score to help perfect modafinil & make Cephalon one of the hottest innovators in the biotech world.

In the early 2000s, Edgar and his team began to develop a line of anti-drowsiness pharmaceuticals that would position Hypnion in the same league as Cephalon.

While modafinil active ingredient represented a breakthrough, Edgar said, “…the first drug in its class is rarely the best.”

At that time, his company was private while in preclinical development. Hypnion scientists didn’t want to voice much about what the pharmaceutical company had in the pipeline. However, just as how Prozac (or fluoxetine) was superseded by Paxil & Zoloft, Edgar believed Provigil would be substituted by finer wakefulness medicines.

Back in the late 1980s, at a time when Dale Edgar first suggested that the brain sleep centers were localized, public reactions to his research conclusions ranged from disinterest to contemptuous ridicule.

Working under William C. Dement [5], the founder of Stanford’s Sleep Research Center and a leading authority on sleep, sleep deprivation and the diagnosis, as well as treatment of sleep disorders such as narcolepsy & sleep apnea, Edgar discovered that the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), the part of the hypothalamus, recognized in 1972 as the brain’s biological clock-controlled not sleep in general but wakefulness.

While working with squirrel monkeys Edgar learned that if one damages the SCN in animals, they mislay their ability to stay alert. Essentially, the SCN works as a tiny alarm clock that rings louder as the day wears on, then falls silent at bedtime.

Despite Edgar’s research, most sleep scientists in the field clung to the concept that sleepiness was only one cause-and-effect mechanism and not a summation of two separate strong desires or urges. From his research contribution, he slowly won over the doubters and finally published his unearthing in the Journal of Neurobiology in 1993 [6]. “I went from university to university giving lectures,” Edgar recollected, “basically being a lobbyist.”

In 2000, Edgar and a colleague, Emmanuel Mignot, left Stanford to establish Hypnion. This company was later acquired by Eli Lilly and Company in 2007 [7][8].

With his car, he moved with his family from Palo Alto to Massachusetts. “I was scared to death,” Edgar admitted. “I’m a third-generation Californian, and I had a tenured position. Here I was moving cross-country to start something that might fail.”

The anti-sleep pills might grab the headlines, but tranquilizers (drugs used to reduce agitation, fear, anxiety, tension, and related states of mental disturbance) called hypnotics would in due course help more users than Provigil. The global market for sleeping pills was considerably larger than for Provigil-style wakefulness boosters. That’s why Hypnion was on the pathway after the ideal insomnia medicine first.

Over the years, the quest for perfect tranquilizers had steered down a little-known detail of addiction & overdose. In the 1970s, barbiturates (a class of sedative & sleep-inducing meds), which are singularly dangerous, were substituted by the benzodiazepines (BZDs) like Valium and Librium. However, BZDs (sometimes called benzos) became known for their negative effects: memory loss, withdrawal, dependence, rebound insomnia, and sometimes paranoia, seizures, & depression.

The principal insomnia medication called zolpidem (Ambien) isn’t technically a BZD. However, it functions on the identical neural pathway, suppressing certain activity across the brain.

At the Associated Professional Sleep Societies Convention held in Chicago in June 2002, researchers exhibited several “novel non-BZD” hypnotics. Most of those meds affected an already familiar stronghold of the brain – the GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid), receptors, which meant they could have been categorized as scheduled narcotics. According to Edgar, as the GABA receptor pathways exist everywhere in the brain, the new non-benzo meds tend to feeble the lights across the entire CNS.

In a search for a truly novel medicine in 2003, the Hypnion company was examining the brain’s sleep-wake pathways to ascertain exactly which of them make finer targets for new medicines [9]. In 2004, its first anti-insomnia medicine, dubbed HY2901, was supposed to be in Phase 1 trials.

David Hangauer, a medicinal chemist, a professor at SUNY Buffalo (a New York’s #1 public university), and an accomplished medicine designer took Hypnion specifications and “started making molecules,” according to Edgar. By using the information obtained through Score 2000, Edgar’s research team progressively whittled down the candidate compounds to a shortlist. “Before, you’d take a large number of molecules, do in vitro tests, and see how they behaved pharmacologically – what the side effects were,” voiced Edgar. “Now we’re building the molecules, so there are no side effects, to begin with.” As stated by Edgar, the results would be meds with almost no potential for addiction or abuse.

In 2003, another competing med was already in trials. The Japanese Takeda Pharmaceutical Company – the largest biopharmaceutical company in Japan & a global industry leader pharma – was testing ramelteon (Rozerem). This drug was being designed to treat chronic insomnia and transient sleep. The company’s goal was to find a remedy that would help its users to fall asleep faster.

Hypnion was pursuing the so-called sleep maintenance meds that helped various individuals stay asleep – the problem for most chronic insomniacs – as opposed to falling asleep. It was believed that because sleeping could be more challenging as patients or healthy individuals aged, the “smart pill” market demand would grow as baby boomers (people born between 1946–1964) got older.

In the end, with Edgar’s revolution on modafinil research based on Hypnion’s lab rodents, it was promising that individuals with sleep disturbances and other health problems would get an effective remedy and an opportunity to control the sleep patterns. However, in the early 2000s, the society was probably not ready for the new generation of sleep medications.

The United States track athlete – Kelli White – was found using modafinil after winning 2 gold medals at the World Track & Field Championships held in Paris in August 2002 [10][11].

Why? It was revealed that Kelli was taking the medicine to combat narcolepsy, but the International Association of Athletics Federations, the sport’s entity-body, was not content with Kelli White’s use of modafinil and classified it as a stimulant drug and recommended she be stripped of her medals. Does modafinil show up in drug tests? Learn more from this guide.

Should you take a “smart pill” to win a competition? Boost productivity? Or enhance your cognitive function? Modafinil is very safe if used by healthy individuals but is best known for treating sleep problems and other health conditions. However, nootropic enthusiasts popularized it as a brain booster.

How can you take modafinil? Well, it works better if you follow the prescription and instructions from a medical specialist. Modafinil is a time pill and the best time to take it is according to a prescription. As to how to sleep on modafinil, it should not be consumed before bed or when preparing to sleep. Modafinil mechanism keeps you awake for about 12–15 hours or more. Timing its use correctly is the single most effective approach you can exercise to ensure it doesn’t keep you up at night. If you’re a 9-to-5er, the most appropriate time to take it is right after breakfast. For more info about modafinil, quickly acquaint yourself with modafinil FAQs.

References:

- List of psychoactive drugs used by militaries. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Wikipedia.org.

- No-go pill. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Wikipedia.org.

- Pilot pill project. Updated: Feb 16, 2011. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Web.archive.org.

- Dextroamphetamine. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Wikipedia.org.

- William Dement, giant in sleep medicine, dies at 91. Published: June 18, 2020. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Med.stanford.edu.

- Effect of SCN lesions on sleep in squirrel monkeys: evidence for opponent processes in sleep-wake regulation. DM Edgar, WC Dement, and CA Fuller. Journal of Neuroscience. Published: March 1, 1993. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Jneurosci.org.

- Hypnion. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Crunchbase.com.

- Lilly Announces Completion of Hypnion Acquisition. Published: April 3, 2007. Investor.lilly.com.

- Hypnion Secures $47.5 Million in Series B Financing. BIOWIRE2K. Published: March 17, 2003. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Businesswire.com.

- Kelli White. Retrieved: July 9, 2020. Wikipedia.org.

- Doping for Seconds. The Shadow of Drugs on American Athletics. Published: Number 6, 2004. Thenewatlantis.com.